Which makes good marketing sense really. What do all readers have in common? An interest in books, of course.

Joyce Carol Oates, in a review in the New York Times, coins the term ‘bibliomemoir’.

Rarely attempted, and still more rarely successful, is the bibliomemoir — a subspecies of literature combining criticism and biography with the intimate, confessional tone of autobiography. The most engaging bibliomemoirs establish the writer’s voice in counterpoint to the subject, with something more than adulation or explication at stake.

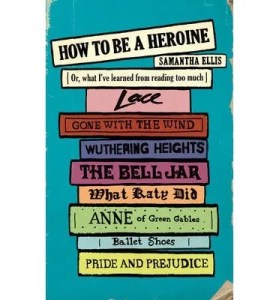

Samantha Ellis’ How to be a Heroine (Or, what I’ve learned from reading too much) ticks all of Oates’ bibliomemoir boxes.

Ellis’ narrator is engaging and witty. She uses the books she read as a child and young adult to tell us interesting things about her own life growing up in the Iraqi Jewish community in London. And then she re-reads and critiques those books as the feminist, literary adult she has become.

…I knew I would have to meet all my heroines again, every last one. I wanted to think about what they meant to me when I was growing up, and what they mean to me not that I’m grown up, and a playwright and writing heroines of my own.

Part of my own enjoyment of this text was that, for once, I had actually read most of the books covered.

This was partly because Ellis was a lover of classic children’s literature (various fairy tales, Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, Pollyanna, Judy Blume) and partly because we were both teenagers during the eighties (Jilly Cooper, Angela Carter, Shirley Conran). So there was some happy nostalgia involved, and I enjoyed being able to revisit some old fictional friends.

Of most interest, though, was Ellis’ critiques of books that she had once loved and now reread from an adult perspective.

Reading that pile of books again, I realised that some of my heroines had misled me, some now seem irrelevant, some I had wildly misread, some I now regret. But many – most – were a pleasure to meet again.

The Valley of the Dolls is bleak while Shirley Conran’s Lace is empowering. Ellis switches allegiance from Cathy Earnshaw to Jane Eyre. Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind stands up to scrutiny but Little Women does not. Finally, someone else has recognised what I knew all along: Marmee was too harsh when she allows Beth’s canary to die, simply in order to teach Beth a lesson about the consequences of all play and no work.

Ellis is an engaging writer; her narrative is full of warmth and sharp insights. Each chapter explores a dozen or more books but How to be a Heroine is only loosely structured by the order in which Ellis originally read each book. Instead, the narrative arc is more about what Ellis learned as she read, and grew, and lived.

Highly recommended.

- For a comprehensive overview of the bibliomemoir genre, try this multi-part blog post at Storyacious.

- Or try The Top 10 Books About Reading, in the Guardian.

Growing up in a family of boys I only read boy books. My adolescence seems to have been centred on Beau Ideal, PC Wren, one of the Beau Geste trilogy and all that frightful frigid stiff upper lip and doing the honourable thing stuff. But I still re-read my old books from time to time, William books, The Saint, a shelf of PC Wren, The Young Fur Traders. I’m not sure I re-evaluate them, just let those endless summer days flow over me again.

Around grade 6 (1962) I even had a subscription to one of the Boys Own magazines for a while, and still remember a cartoon serial about a family in the trucking game Knights of the Road, and look where that got me.

All of those passed me by, I’m afraid. It was pony books for me…. https://michellescotttucker.com/2014/07/18/vale-josephine-pullein-thompson/

[…] How to be a Heroine – Samantha Ellis (Engaging narrative voice) […]

[…] How to be a Heroine – Samantha Ellis (Engaging narrative voice) […]